Day For Night, Christiania, 1996 | Online Presentation

In 1996, twenty-five years after its inception, Joachim Koester photographed the community of Christiania. Founded in 1971 as a free-state, Christiania quickly became a symbol and living monument to many of the values and ideologies present within Denmark at the time. In some ways, it never left this ideological state, still full of potential while falling into ruin at the same time.

Koester’s documentation created a series of thirty-five photographs, which he named Day for Night, Christiania, 1996.

Later this month, the gallery has the pleasure of presenting all thirty-five photographs of this iconic series, at Chart Art Fair (Copenhagen, August 30 – September 1) which marks the first time that the work has been presented in its entirety. The following Online Presentation explores the history of the work, as well as the shifting landscapes and contexts of Christiania.

Concurrent with this Online Presentation is a filmed conversation conducted this summer between Joachim Koester and Nicolai Wallner on the impact of this work, and the importance of Christiania.

Christiania was established in 1971, with the takeover of a derelict military complex east of downtown Copenhagen. Declaring itself an autonomous, free-state, the group of activists who founded it were intent on creating an alternative, utopian city within a city, furthering many of the existing ideologies that were present in Danish society at the time.

In 1996, when Joachim Koester began documenting Christiania, it had been in existence for 25 years. Much of the original principles on which it was founded were still in practice, still full of potential and still waiting to be fulfilled, while much of it had never come fully into fruition.

Echoing this discord, much of the area was similarly in disarray. Buildings were both being constructed and falling into ruin at the same time, abandoned and unfinished, while simultaneously being organised and used by a vibrant community who were content to live within this in-between state. Together, they had established a strong network of institutions, including daycare, cultural centres, concert venues, places for workshops, cultural events and cafés, which ran alongside a well-organised, open hash market. These institutions were accessible not only to those who chose to live in Christiania, but anyone who wished to participate, making it an attraction within Copenhagen as well as a tourist destination, creating an influx of people coming in and out of the community.

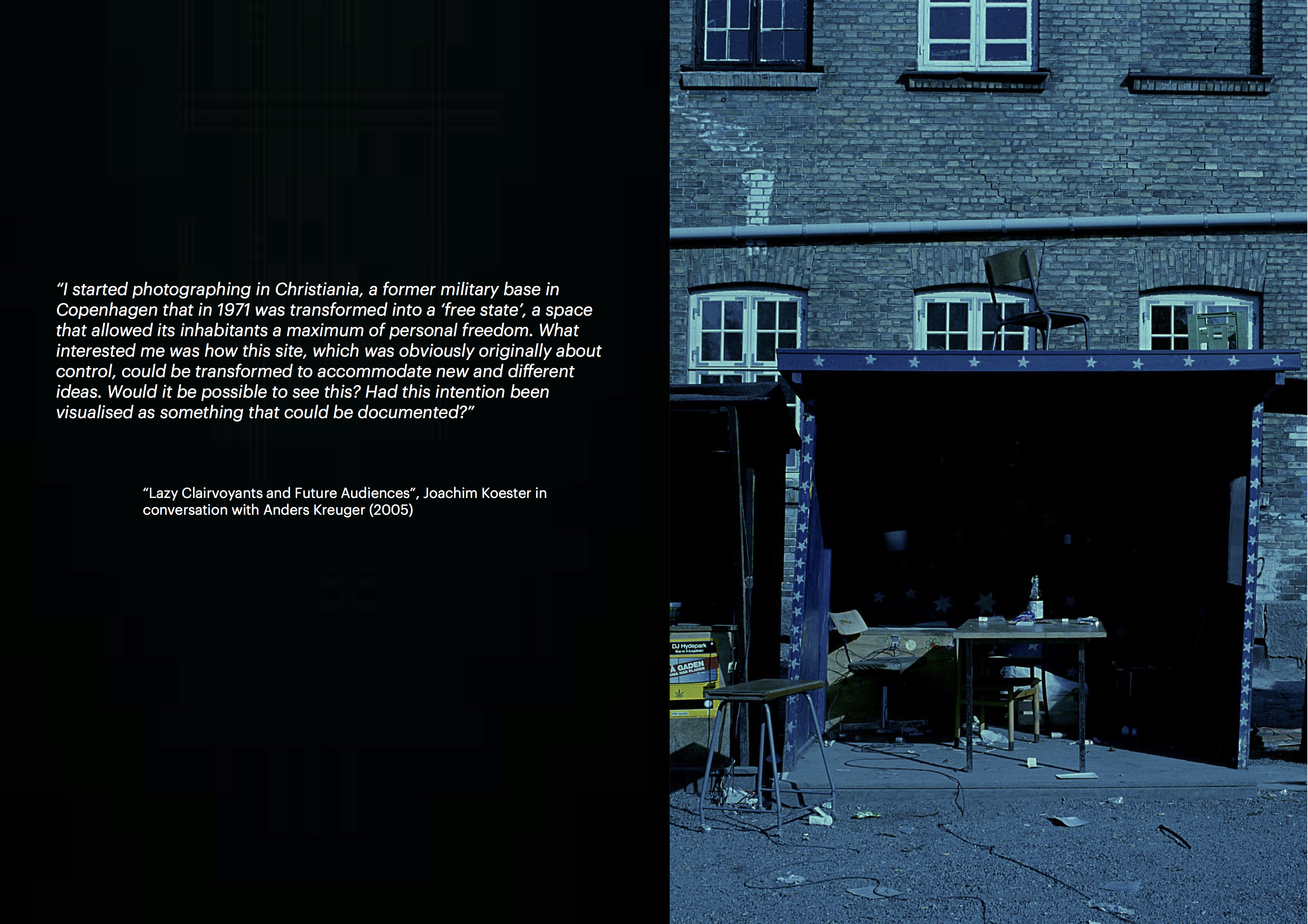

It is this in-between state which is at the centre of Koester’s work. Comprising of thirty-five photographs, Day for Night, Christiania, 1996 feels other-worldly. Almost entirely devoid of people, the photographs focus on the buildings and greenery of the area, each appropriately named after its subject. The resulting titles are both poetic and practical, for example “The Milkyway / Officer’s Quarters” and “The Peace Ark / Barracks”, reflecting the locations’ militaristic backgrounds and their re-imagined purposes.

We too, are left to imagine what could have been and what could still be. A landscape of lush forest, plastic lawn chairs and picnic benches, graffiti, paths leading to seemingly nowhere, temporary structures left in semi-permanence and an idyllic lagoon all come together to create a narrative which Koester deliberately leaves open.

Within this context, Koester’s Christiania is depicted with an almost dream-like, cinematic quality. Under a canopy of blue, we are caught between contrasting elements—day and night, fiction and reality, utopia and dystopia, control and chaos.

These tensions remain unresolved, or rather are left to run parallel alongside each other. This concurrent duality, perhaps, is the most telling aspect of Koester’s work.

Christiania was based on a principle of overriding freedom, and in so doing created a place in which everything was made simultaneously possible. One could argue that this is still true of Christiania, as is also true within Koester’s work—we have the freedom to find and choose what it is we want to see.