Moki Cherry

Galleri Nicolai Wallner is pleased to present a solo exhibition of works by Moki Cherry. Moki Cherry (1943 – 2009, Sweden) worked between mediums, bringing together art, architecture, design and music.

Describing her life, work and practice as intertwined—“home as stage and stage as home”—themes of functionality, spirituality and everyday life came together to create immersive and dynamic works that were meant to fit into multiple contexts and places. These intentions and social underpinnings of Cherry’s vision are increasingly relevant today. Alongside her partner and frequent collaborator, musician Don Cherry (1936 – 1995, USA), Moki’s works adorned musical stages, homes, theatres, art galleries and a multitude of other venues from the 1960s onwards, throughout her life.

The exhibition is accompanied by a “Sewing oneself around the Earth organic – A note about Moki Cherry and her work” by Lars Bang Larsen, which can be found father down this page.

Moki Cherry

Title Unknown (Fabric Sculpture from Utopias & Visions) (1971)

Stuffed silk fabric sculpture

203 x 376 cm

To Inquire

Organic Music Society on tour in schools in Sweden (1970s)

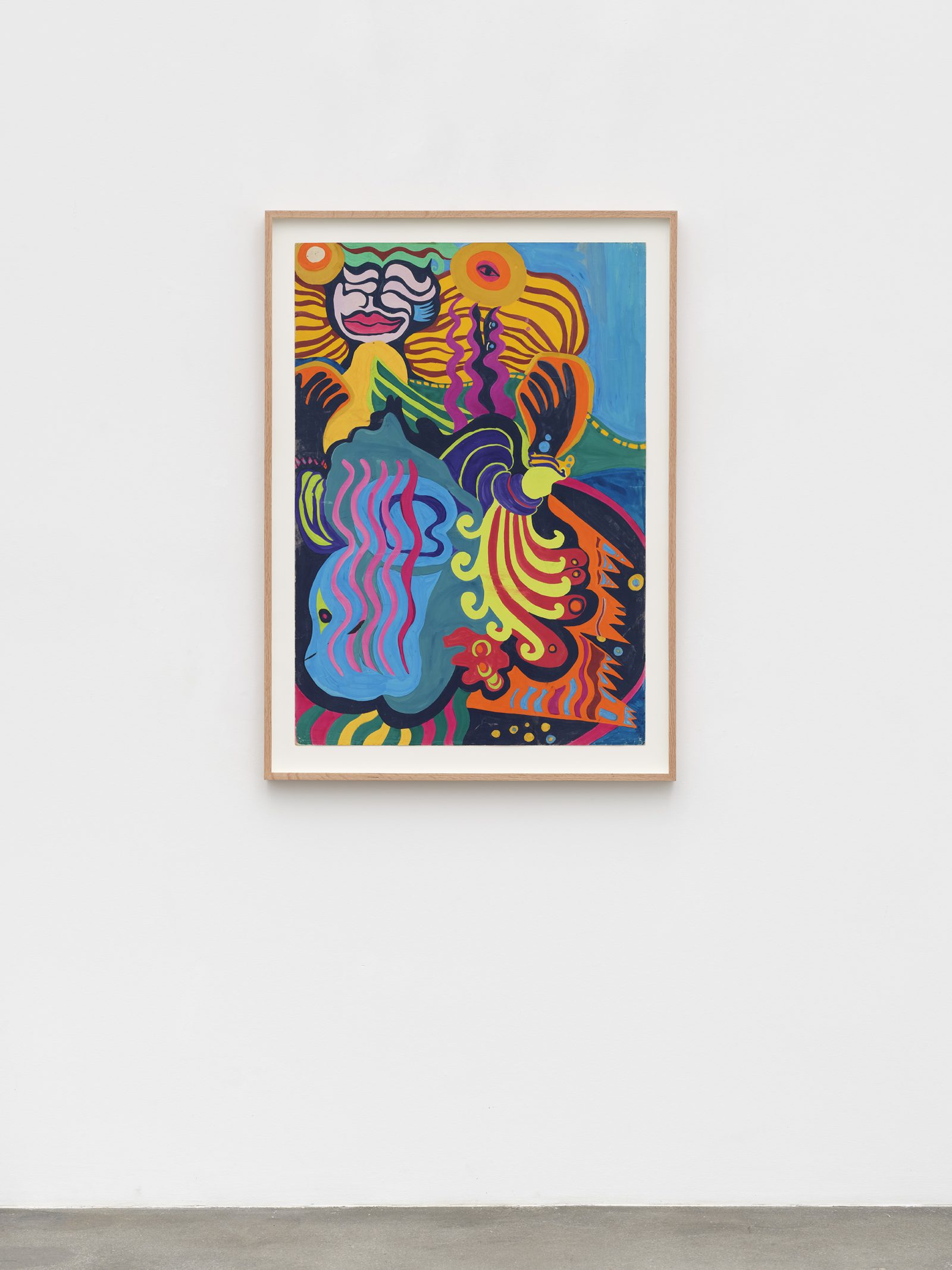

Moki Cherry

Organic Music (Don Cherry, Nana Vasconcelos, Moki, G. Pramaggiore) (1975)

Textile appliqué

102 x 69 cm

To Inquire

Organic Music Society on tour in Italy (1970s)

Moki Cherry

Title Unknown (Tibetan style ceiling canopy) (1977)

Textile appliqué

120 x 240 cm

To Inquire

Sewing oneself around the Earth organic

A note on Moki Cherry and her work

Lars Bang Larsen

This exhibition makes for a return of sorts to Denmark for the work of Moki Cherry (1943 – 2009). Born Monika Marianne Karlsson, the Swedish artist led an itinerant life that saw her pass through Copenhagen as a frequent port of call because of the jazz scene here, to hang out at the Christiania district, or to stage performances at Charlottenborg.

The present exhibition mainly consists of appliqué tapestries, but Moki also created—among other things—ceramics, graphics, paintings, wood sculptures, scenography, and photo collages. Textile was a point of departure, though: she was trained as a fashion designer at Beckmans School of Design in Stockholm. Especially during the 1960s and 1970s, her multiform needlework proliferated in her surroundings.

Moki’s art developed from a domestic situation that was open to the world through collective being and collaborative doing. Her formula for this domesticity that was intersected by multiple bodies, gazes, and gestures, was: ‘The stage is home and home is a stage’. In this way her art played out in the “singular plural”, to use philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy’s term, that is, in the possibilities and contradictions between individual and group that exist when the artist’s “I” doesn’t pre-exist a “we”. Central to Moki’s singular-plural authorship was the question of communication: how to create new forms for it, and to acknowledge other communicating subjects, including women and children. As she wrote in a later text piece, ‘If the walls / if the hours / if the womanhood / spoke / the walls would crack’.

While it would be unfeminist to mention a woman artist’s partner at the beginning of a text about her, as if she or her work weren’t good enough, it can be defended to introduce Don Cherry, and their children Christian, David, Eagle-Eye, and Neneh sooner rather than later. Don was a musician who recorded with Ornette Coleman and Sonny Rollins, among other jazz greats, and the Cherrys hung out with heavyweights of mid-20th century bohemia such as Allen Ginsberg, Niki de Saint-Phalle and Alejandro Jodorowski. A mixed race couple, doing their thing and travelling the world, the Cherrys seem like genuine denizens of the Aquarian age. With its celebratory sensuality Moki’s work meets expectations of a period-specific aesthetic, say with its psychedelic use of letters and words as ornament-images in vivid colours. However it has other and deeper dimensions than a relation to a zeitgeist.

The Cherrys lived and performed together, and gave in 1971 the name The Organic Music Theatre to their mix of communal art making, social and environmentalist activism, pedagogical activities such as children’s theatre, and pan-ethnic expression of world music. “Organic music” compares to other expanded categories for experimentalism at the time, such as the idea of a living theatre, and how visual artists eschewed conventional art media in favour of “concepts”, happenings, and other modalities conducive to alter not only expression but also the situation of the audience. Art needed new relations with the world, and new reasons to be made—for instance so you could sew yourself ‘around the Earth organic’, as Moki wrote.

Outfits and stage designs for The Organic Music Theatre’s performances were Moki’s doing. Malkauns Raga from 1973, for instance, was presented together with five other tapestries as a backdrop and for audience engagement at the Theatre’s gig at the Newport Jazz Festival that same year. In photos of the Cherrys and their fellow travellers, her textiles appear like some otherworldly scenography, whether it was hung between VW buses at a campsite or installed at a music workshop with school children in some drab Scandinavian suburb. The individual piece played its part in soft arenas and immersive environments that were made for other activities, but was at the same time self-sufficient enough to hold its own wherever placed.

It is only recently that art textiles are becoming legible to the art institution as something else than aberrant craft. And although integrated expressions, such as the synthesizing of visual art and performance through music, stagecraft and painting, are significant avant-garde traditions—and one that Moki was aware of—her work was often considered a visual embodiment of Don’s music. This is an inadequate (if not somewhat sexist) assessment that sees it as derived and supplementary, not original. This is not to say that her work did not correspond with the music around it, but Moki’s was a reply of a more radical character. In her own words, her work was attuned to the energy of the present moment, ‘the progress of the now’, as she evokes it in a poem from the late 1970s.

This translates well to improvisational practices such a free jazz. Cultural theorist Fred Moten groovily characterises improvisation as a sort of collaging of temporalities: ‘Improvisation is located at a seemingly unbridgeable chasm between feeling and reflection, disarmament and preparation, speech and writing…improvisation, in whatever possible excess of representation that inheres in whatever probable deviance of form, always also operates as a kind of foreshadowing, if not prophetic, description.” [63] In this drama of binaries stretched out in time, Moki’s work is placed on the side of preparation, reflection, and writing. She engaged with the now of the music with her own tempos, suturing transient events and inhabiting the boundaries between art and music, live performance and visual form, stage and domestic space. This is how Moki’s works tangled with the context of their making with an exuberance that continues to make good on some of the promises and intense living from back then, in their own right and their own time. It called up bigger temporalities, too: She commented in retrospect on her use of Buddhist imagery that ‘I liked the idea of making an image that thousands of other artists had made before and will continue to create’, as if her production of images was a kind of cosmic ephemera, connected to other makers and generations in ever widening cycles of renewal.

As late as the 1990s she wrote in one of her word pieces, ‘I am OK I have career ahead’, a note to self that speaks of a feeling of artistic isolation. Now we can see that she wasn’t alone in what she did as a visual artist. Marie-Louise Ekman and Charlotte Johannesson are other Swedish artists of the same generation whose attitude to art making can be compared to Moki’s: unworried experimentalists who drew on crafts traditions and other creative disciplines, as well as the wider social context for their work, to develop original feminist styles.

Moki didn’t reserve particular media or sites for her work, but let creativity loose indifferently of place, material and circumstance. Her fabrics travel with a history that makes you look back to the bodies they wrapped and the situations they framed, but they also make you aware that you need to look ahead from our present moment, ‘with a kind of torque that shapes what’s being looked at’ (Fred Moten again). This gaze situates her works as entities moving through history, in their continuous bending of time and foreshadowing of what is to come.