In mid-October 1993, Galleri Nicolai Wallner opened its doors for the first time in downtown Copenhagen. On the occasion of the gallery’s 30th Anniversary, we look back at the artists, exhibitions and important moments that have shaped its history.

The following essay examines the political, social and cultural contexts of year in which Nicolai Wallner started the gallery, and explores how this shaped the formation of the gallery then and how they have continued to do so today.

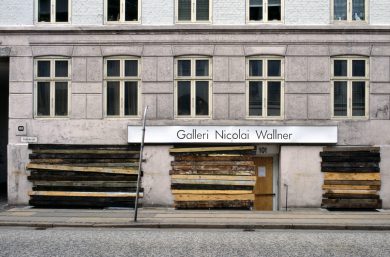

Work by Joachim Koester for the exhibition “Stain in Reality” (1994) at the gallery’s original location

Cultural progression is defined by the moments when radical changes occur—the moments when existing ideologies and practices are deemed archaic and necessarily replaced by newer systems. An analysis of our contemporary culture is in many ways dependent on the reasons behind the shift to a current system. In other words, to understand what our culture produces, how it is exhibited, received and interpreted, there must be an understanding of why the old system was abandoned, and how the current system came to be in place. Such a paradigm shift occurred in Copenhagen in 1993. The scale of this cultural shift was substantial, as it would encompass two equally important, simultaneous, yet independent shifts—one that would occur within the group of young, new artists working at the time and another that would occur within the realm of the galleries. The aim of this essay is to delineate the contextual elements that came together to produce such a paradigm shift within the gallery culture of Copenhagen, and subsequently how this would affect the parallel shift within the up and coming group of artists working in the early 1990s.

Initiating such a change within the working practices of the galleries was Nicolai Wallner and the gallery he would open in October of 1993 in Copenhagen. Now, 3o years later, the origins of Galleri Nicolai Wallner are again in focus. This is not the simple marking of an anniversary. It is instead an opportunity to re-examine what made the shift so decisive, and provide us with a better understanding of our current cultural production.

1993 was the setting for many political and social transformations throughout Denmark. Consequentially, the capital city of Copenhagen became a kind of poster child for the early 1990s as the harsh realities of the 1980s set in and Danish society was forced to confront much of what it had ignored the previous decade. While the political and social events that occurred in Denmark in 1993 were not individually fundamental to the cultural paradigm shift, they provide a backdrop and were the source of a sense of disillusionment that engendered the new generation of the early 1990s. In hindsight, what would make these events important was not so much what happened, but rather how this new generation chose to react in opposition of them.

These sentiments echoed around the world, as 1993 also marked a state of political and social upheaval elsewhere. In the Americas, Bill Clinton was elected President of the United States. The World Trade Center was bombed for the first time, injuring thousands. Race was at the forefront, as the white police officers charged in the beating of Rodney King, an African-American went on trial, and the continent as a whole dealt with issues of gender and the spread of AIDS. Europe was dealing with the aftermath of the end of the Communist regime, as the Bosnian War reached it’s halfway mark, the last of the Russian troops left Poland, large uprisings were held across Serbia against Slobodan Milosevic, and the state of Czechoslovakia dissolved, creating the Czech Republic and Slovakia. The world was in the midst of a change, and with it went Copenhagen.

However as much as these seemingly catastrophic events helped define Copenhagen in 1993, what would mark the year would not be political or cultural unrest. The 1980s had also proven to be tumultuous, and in that sense there was little difference between the unrest in 1993 and the unrest in the previous decade. Nevertheless, something was a different. The difference would be in the reaction that the new generation of 1993 would have in regard to the unrest in their environment.

The idea of the gallery came to Nicolai Wallner when he was still finishing high school in Copenhagen. At the request of a teacher, Wallner and fellow students began exploring local art institutions and galleries. Wallner was immediately struck by the lack of contemporary art that was to be found in the established galleries, and soon began exploring more alternative spaces where such art might be exhibited. What he discovered was a strong network of artist-run spaces run by contemporary artists, and he was immediately fascinated both with the artists that ran the spaces, as well as the works that they were exhibiting in them.

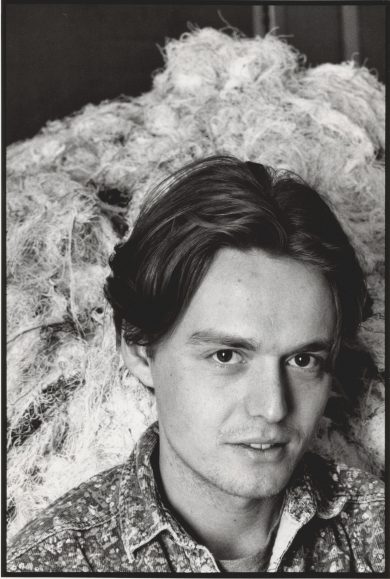

Nicolai Wallner in 1993 at the gallery’s first exhibition

Coming from a middle-class background where he had not been formally introduced to art, this new world was foreign, yet the nature of these artist-run spaces allowed Wallner to immerse himself completely. As the artists exhibiting in these spaces were often the same artists who were running them, they could usually be found alongside their works. This provided Wallner with the opportunity to interact with the artists directly, and allowed him to begin a dialogue with them about their practice. Wallner was impressed by the accessibility and honesty that he felt these works evoked, and it left him wondering why these works were not being exhibited in the more established galleries in Copenhagen.

This came at a time when Danish society as a whole put great importance on receiving an education that would lead to positive, useful production, an idea that had been heightened as a result of the economic crisis of the 1980s. As a result, less traditional forms of employment, such as “artist”, were seen as existing on the margins of society, if not separate from it entirely. The production of contemporary art was conceived of as irrational in the sense that it had a conceived lack of function outside itself.

This is not to say that artistic production was not valued, rather that this new generation of artists had begun making works that had little bearing on that of their predecessors, and were therefore hard to contextualize at the time. The tendencies of the more traditional art galleries in Copenhagen underlined this further, as they had little interest in exhibiting this new generation of artists. Alternately, they chose to exhibit previous generations of artists who were already well established. This in turn was significantly limiting the exposure that this new generation had, pushing them farther into the margins.

The artist-run spaces had provided a band aid solution for this lack of representation, but after a long run of initiating and maintaining their own exhibition spaces, the artists were growing disheartened with the time and energy spent running these spaces, time they felt would be better spent on their work. What Wallner aptly recognized, was that there existed a void within the existing gallery culture of Copenhagen. This new generation of contemporary artists needed representation. What was missing was a gallery that had the initiative to take them on and Wallner believed that he might be the right person to take on such an initiative.

Nicolai Wallner’s first step, along with artist Jakob Kolding, was to intermittently use a communal space located in the basement of Wallner’s apartment building as a temporary exhibition space. The space, which they called Gallery Campbells Occasionally, would be the location of several influential early shows, and they began producing a mail-order catalogue through which they would sell contemporary art that could be sent through the mail. The space and the catalogue began to gain notoriety, and soon artists were reaching out to Wallner to exhibit in the space and put their work in the catalogue.

The experience would confirm Wallner’s ambition to open a commercial contemporary art gallery and in 1993, on the back of the success of Gallery Campbells Occasionally, Wallner and a select group of artists decided to open a new, permanent gallery space. The origins of this gallery were very much like the artist-run spaces that existed at the time with money collected every month for rent and kept in a cigar box, yet Wallner soon began experimenting with what he believed would be a successful, alternative approach to running a commercial gallery. The aim of Galleri Nicolai Wallner would be to take what was happening in the artist-run spaces and bring it in to a permanent, established space where more emphasis would be placed on the role of the gallerist. Existing galleries were organized like dealerships, with a continuous cycle of art that was brought up and displayed until it was either purchased or put back in storage. In contrast with this practice, Wallner wanted to create a gallery that would be modelled like an agency.

Wallner wanted the gallery to be involved in a more active capacity instead of simply providing a space where artists could exhibit their work. The gallery would work with the artists, help with production costs, take on a greater role when organizing exhibitions, and, above all, provide strong representation. Wallner conceived of art as a means of communication. Thus art was dependent on being involved in a dialogue, and therefore dependent on an audience willing to discuss it. This new generation of artists needed to be introduced into a wider dialogue. Subsequently, what would be very important from the beginning was that the gallery should ensure that the artists and their works were brought into the public eye—within Denmark but particularly within the rest of the world.

In a parallel movement with Wallner’s desire to create a more dynamic, active gallery, there was also a shift amongst the new generation of artists in Copenhagen who shared the sentiment of wanting to be active, and to participate on an interactive level with what was happening in their own environments. Breaking from the stagnant traditions of the generation before them, these artists chose to make works that reflected what was happening around them. The political and cultural climate of Denmark now became highly relevant. The public, artists included, felt a sense of disillusionment towards what was happening politically and socially at the time. Danish society has always placed great value on the ability to criticize constructively. As Denmark is a welfare state, children are taught in school that they should be active participants in society. One of the most direct ways of engaging in such participation is to be critical and questioning of what is put in front of you—to participate in an open dialogue about culture and politics, to be constructively critical of what is going on in your own environment. This sense of disillusionment towards the political and social climate that was felt both by the artists and by the general public in Copenhagen was channelled into constructive criticism. This is one of the defining factors that made such a double paradigm shift possible. It was no longer enough to simply be frustrated or upset by an event, rather it was necessary to enter into a dialogue, to produce something that would take a stance against what was happening. With the work this new generation of artists were making and the way that Galleri Nicolai Wallner was being run, they effectively entered into the dialogue.

The idea of art entering a social dialogue would demand a more interactive participation from the spectator. These new artworks that the new group of artists were producing were very dependent on creating an interactive experience and on forging an emotional connection through the works. Exhibitions took on a new level of importance, as they were where the artist, the works and the spectator interacted. The gallery would provide this kind of space.

The gallery could thus be interpreted as a source of inspiration, rather than a restriction. The gallery would correspondingly take on many of the roles that had once been occupied by the studio. The works that were being created were no longer necessarily made in an atelier, but were increasingly site-specific and installation based. The artist was no longer stereotyped as an isolated genius, creating works laboriously in his studio. Instead the new contemporary Copenhagen artist was an important social figure who now provided a critical opinion within the public arena.

Nicolai Wallner and Jacob Fabricius at the art fair Artforum Berlin in 1996

The more the works produced began to reflect their environment, the more important it was for them to be exhibited in that environment. Artists started producing more works that were created for specific spaces and for specific exhibitions. Using a variety of materials, many of them unconventional, also meant abandoning a traditional studio. Works did not necessarily need to be produced in the confinement of the studio. Correspondingly, the gallery and the exhibition space became the primary venue for this production.

At the gallery’s first international art fair in Cologne in 1994, the reception of the gallery, the artists represented and the works exhibited were very well received. This would prove as a testament not only to the art that was being produced at the time, but also as a testament to the direction that the gallery had taken in how it understood its role and subsequently the position it took in representing these new artists.

In hindsight 1993 was a groundbreaking year. What Wallner had recognized and what had been confirmed in Cologne, was that this new generation of artists were in the midst of a radical, important change, and that the resulting works needed to be included within a larger, international dialogue. However, what Wallner could not have predicted was how his own changes to the gallery culture would equally bring the gallery into this dialogue. Now a decisive force, the gallery was no longer a passive entity. By providing the necessary intersection between the artists and the public, between the local Copenhagen scene and the international art world, the gallery would cultivate this dialogue. Galleri Nicolai Wallner would provide necessary backing and confidence in both the artists as well as the works they were producing.

In many ways, both the gallery and the artists would help one another accomplish their respective paradigm shifts, each pushing each other to do more, to become more involved, and to expand and deepen this new dialogue. This symbiotic relationship can in part be credited for the magnitude of these paradigm shifts and the resulting relationship between artist, gallery, artwork and spectator.

30 years later, the contemporary art scene is still marked by what they simultaneously put into place. The principles which guided the creation of Galleri Nicolai Wallner are still visible and can be seen throughout the gallery’s program and vision.

The following article was written by Louise Steiwer for Kunstkritikk in September 2018 in connection with the gallery’s 25th anniversary, with images by Maria Bordorff.

– I saw that there were people in the art world who needed me

Twenty-five years ago, the 22-year-old Nicolai Wallner sat in a damp basement room in Store Kongensgade in central Copenhagen with a pile of small slides he had just had developed in the local photo shop. He arranged the slides carefully in plastic sheets, placed them in a lined envelope and put on a stamp. In just over a week they would arrive at the home of the British customer who had gotten in touch earlier that day via fax.

Fast forward to the present day: Kunstkritikk meets Nicolai Wallner in his new, vast exhibition venue on Glentevej in Copenhagen, an area otherwise characterised by dilapidated industrial buildings. The setting seems far removed from thescene of the young man tending to his plastic sheets in a basement room. The gallery space is currently home to Alexander Tovborg’s most recent productions – two paintings, each of them six metres long – and in the back room eight assistants are perched at their Apple computers, busily turning the wheels of the vast machine that is Galleri Nicolai Wallner today.

Nicolai Wallner in the current gallery space, photo by Maria Bordorff

Had this been a reality TV show, we would probably describe the evolution of Galleri Nicolai Wallner as ‘a journey’ – one that began in a basement and ended up on the pinnacle of the international art world. Launching his gallery in October of 1993 – which means that the gallery’s 25th anniversary is just around the corner – Wallner had his first opening at the art fair in Cologne in 1994. His project met with much keener interest abroad than back in Copenhagen, and so his dream of becoming the nation’s largest international gallery was born.

The gallery moved from Store Kongensgade to a ‘real’ exhibition venue in Njalsgade in the Islands Brygge neighbourhood, later relocating to almost Kunsthalle-like premises on the city’s Carlsberg site before recently arriving in the Nordvest district.

Through the years, Nicolai Wallner has been involved in numerous major projects outside the gallery itself. Taking his starting point in his own early beginnings as an artist-run gallery, he rented buildings at the Carlsberg site that not only accommodated Nils Stærk and Wallner, but also made rent-free premises available to the artist-run IMO and accommodated the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts’ exhibition venue BKS Garage. This was also the birthplace of his and architect Kristoffer Weiss’s joint vision of setting up a new municipal Kunsthalle – a project which was on the cusp of fruition several times over the course of ten years of negotiations with the City of Copenhagen, only to finally crumble when the plans for the remodelling of the new cultural district on Papirøen were done.

Today, Galleri Nicolai Wallner is a regular feature of artfairs such as Art Basel, Armory Show and Frieze Art Fair, presenting international figures such as Dan Graham, Daniel Buren, David Shrigley and Jonathan Monk alongside his roster of Danish artists, which currently includes A Kassen, Elmgreen & Dragset, Jeppe Hein, E.B. Itso, Jesper Just, Joachim Koester, Jakob Kolding, Peter Land and Alexander Tovborg. The most recent additions to the gallery’s list of artists are Marie Lund and Poul Gernes Estate.

In many ways the story of Galleri Nicolai Wallner reflects the overall story of the Danish art scene’s shift from the active, self-organised scene of the 1990s, an era generally dominated by an economic downturn and a continued focus on the dominant ‘young wild ones’ of the 1980s, towards our present day where interest in contemporary art seems greater than ever, where the distance from art academy to museum has been minimised, and where Copenhagen has become an art destination in its own right.

Kunstkritikk took a trip back in time with Nicolai Wallner in order to find out how he first became acquainted with the world of art, how he picks the artists he wants to work with, and what he thinks about the Danish art scene today, having run a gallery for twenty-five years.

How did it all begin?

Before opening the gallery back in 1993 I had already run a project space, Campbells Occasionally, with artist Jacob Kolding. We were still in high school, and the space was located in the basement of the building where I lived with my mother and brother. Back then we weren’t part of any kind of scene at all, but through some of the artists we presented there I got in touch with a group of people from the art academy and began to hang out with them more. They included Peter Land, Christian Schmidt-Rasmussen, Jes Brinch, Thorbjørn Bechmann, Jens Haaning, Henrik Plenge Jakobsen and Jonas Maria Schul, and they were interested in opening a gallery. What I had done before wasn’t really a proper gallery: it was basically a matter of borrowing a rental party venue and then staging small exhibitions for 14 days at a time.

The idea was that I would run the gallery and they would fulfil the role as artists affiliated with that gallery, but during that first year we all ran it together. We later decided that I would run the place, which already bore my name. In fact, it was the artist’s idea to not call this whole thing ‘Project so-and-so’; they wanted to convey the message that this was a real, proper gallery.

What were your reasons for engaging with that project?

David Shrigley, “Life Model” installation view, 2014

I wanted to work with artists, and I was perfectly happy to do all those admin jobs that the artists didn’t want to do themselves: opening doors, running exhibitions, sending out invitations and presenting the art to the wider public. I would also act as what you’d probably call a ‘manager’ back then, but which we now call ‘representing’ the artists. No-one did that in Copenhagen at the time. Many of the commercial galleries around that time were more like art dealers where artists would put on a show that might or might not sell, and then they’d be off again. Most places didn’t engage in the kind of practice that I was interested in: representing artists in every respect, tending to all their needs and interests right from presenting their art in the gallery to helping them getting their works produced and assisting them on a more private, personal level. I was hugely interested in that aspect of things.

Few eighteen-year-olds have that kind of certainty about what they want to do. You saw that you wanted to work with art from a very early stage – why do you think that is?

Yes, it was very early. I had a super-inspirational teacher in high school who taught literature and art. He urged us to get out and look at art in museums and at artist-run venues. I and some friends visited small, artist-run places. We’d enter these rooms to find something on the walls and some artist minding the exhibition. We thought that was quite a privilege, really – going to see a show and actually meet the person who’d done the works and was able to tell us more about them. We were really young, sixteen or seventeen, and we didn’t know anything about the art scene or its conventions, so we just asked away: what’s that? Why are you doing that? Why is the price of this one set at 9,000 kroner? Why do you want to be an artist?

We asked all sorts of questions that come naturally if you’re curious about art, but which you might not ask if you begin to work with art later in life. It taught me about what it means to be an artist, and in my case that made a huge difference. I realised that I wasn’t just interested in the art itself, but also in the artist, in the artist’s conditions, needs and motivations.

Growing up in a middle-class family in 1970s Denmark like I did, you were brought up on the idea that it was important to get a college education so that you could go on to hold an important function in society. It was a great eye-opener for me to meet these people who weren’t part of that system or mindset, and who weren’t productive in the sense that I was brought up to be. The artists I met were extremely productive, but they did so without prompting. I was very fascinated by the fact that there was this group in our society who created something without being asked to, and that they did it for our sake, at least partly. Everything else that’s being done in our society is based on some kind of demand. If artists stopped making art, it would take quite a while for anyone to notice. But if kindergarten teachers stopped looking after children, society would instantly collapse.

Bear in mind that at that time, some twenty-five to thirty years ago, being an artist was in no way fashionable. You didn’t choose to be an artist because it was cool. Back then, being an artist was just one step above being on the dole; there was no respect or fascination with the profession the way that you see today. Many of these people – and this may still be true to some extent – ended up as artists because they couldn’t quite settle in anywhere else in society.

Back then, did you envision the gallery growing as big as it has?

Yes, absolutely. I wanted that right from the get-go.

Where did that ambition come from? The way that you tell it, there weren’t many sources of inspiration in Copenhagen?

“Odd size” group exhibition installation view, 2011

When I’d just left high school, I began to look towards galleries in Cologne and New York, which were the main art capitals of the world at the time. I hadn’t visited New York, but I went to Cologne and visited the type of galleries that I myself was interested in creating. Galleries that are not primarily about selling objects, but about working with the artists.

Part of the reason why this particular work appealed to me probably had to do with my rather over-developed caring streak. I’m sure that’s got to do with the fact that my father died before I was born, which was of course a huge tragedy for my mother. Growing up in a family infused by a mixture of joy that I was born and grief for the death of a husband made for a psychologically complex situation. Children sense that sort of thing. I think it gave me this abnormally huge need to care for others. In the art world I felt that someone needed me. This definitely helped me make up my mind about what I wanted to do at such a tender age. I was also so tremendously busy making the whole thing happen that I never had the time to think about whether the it was realistic at all. I think that there’s a dash of a fear of dying in the mix, too. Today I don’t think I have any more anxieties about dying than most people, but back then I felt I had to do a whole lot in very little time. I think that’s embedded in my family history: you don’t know how long you’ll live. So I’ve been in a real hurry to move forward.

The early 1990s were a time of economic austerity. Launching a gallery at that point can’t exactly have been a licence to print money?

We certainly didn’t sell anything. At all. I think our sales during the first year totalled 1,500 kroner. Of course, this meant that I had to make my living in other ways, so I picked up a slide projector and toured the folk high schools of Denmark with lectures on young Danish art. That way, I made enough to pay the rent. There are also certain advantages to getting started during a slump. For example, no-one would lend us any money, which meant that we had no debt at all. I learnt that you have to make money before you spend it.

When did things start to pick up for the gallery?

That rather depends on what your yardstick for success is. It was really hard at first, but on the other hand things were really simple and easy too. For example, it also meant that none of the artists got the idea of staging an exhibition that would cost 100,000 kroner to produce.

A few years ago, I saw the exhibition NYC 1993 at New Museum. It was about the New York scene of 1993, the same year that I opened my gallery in Copenhagen. Seeing the sheer amount of DIY around at the time was one of the really thought-provoking aspects of that exhibition. Everything was produced by the artists themselves and made out of cheap materials, and that didn’t harm the exhibition one bit – quite the contrary. You could do anything you liked, just as long as it didn’t cost anything, which of course means that the art takes on a different feel. It was a time of ‘everything goes’, perhaps with the exception of 1980s painting, and that led to the creation of some super-exciting things. It’s a little like doing a Dogmefilm: when there’s no money to spend, you find a whole range of other options opening up to you.

Things have changed a lot since then. For us, of course, but also for those who start a gallery or make art today. I think things have gotten harder; if you open a gallery today, there are all these very clear expectations about what you’re supposed to offer. You need high ceilings, good lighting, and perhaps your artists want to do things in bronze that are very costly to produce. There’s more money around today, but that also means that things change a great deal compared to how they used to be.

How do you decide what artists you want to work with? And have your criteria changed over time?

Our initial group was actually rather a random accumulation of people who just happened to know each other from various contexts. Today I still represent Peter Land, who’s been on board right from the beginning. I later found that there were other artists I wanted to work with, just as there were some artists among the original group that I didn’t want to work with. Some partnerships ended there, but I think that my criteria are the same now as they were then. Quite simply, it’s about artists whose art I am interested in working with and presenting to wider audiences. I spend such a lot of time and energy on it, so it’s important that I’m 100% on board with it; that I really feel it. Twenty-five years is a long time to spend working with the same artists. I’ve spent more time with many of my artists than most people do in their romantic relationships.

Whenever people first become interested in the work of a particular artist, they have no way of knowing which direction that work will eventually take, and they also don’t necessarily know how their own tastes will evolve. What sort of deliberations do you entertain when you eye up an exciting art practice before entering into a partnership?

“Jump” group exhibition installation view, 2017

That’s precisely what makes it so difficult to make that decision. There have been times where I’ve been very reluctant to launch new partnerships. And that reluctance has been based on the premise that the number of artists I can work with is restricted by my resources – my own and my staff’s. I’m no longer quite as worried about disappointing people that I once was, but in the past I’ve wanted to be absolutely sure that all collaborations were satisfactory for both parties, and this has probably made me too cautious at times.

There are lots of artists out there who I find interesting and exciting. Many of them aren’t necessarily artists that I would be interested in working with, and in some cases I see that even though I find them interesting, I wouldn’t be able to give them the kind of push they need. And then there are some artists who strike me as exciting, but where I prefer to wait a bit and see what they get up to. For example if they’re very young.

This isn’t the kind of gallery where artists are taken for a trial run before an actual collaboration commences. Once I start working with someone, the intention is for that partnership to go on for years and years. I never do a trial exhibition with an artist just to see how things pan out before entering into an agreement.

Why not?

I think it would unfair to the artists, to the people visiting the gallery and to me. I realise that many other galleries do it like that and that it works for them, but it would feel wrong to me. I guess I feel like that about a lot of things here in life: I’m a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ kind of person. I don’t really do well with ‘maybes’.

Is there a difference between the Danish artists that you represent, and for whom you’re the main gallerist, and some of the international artists who are even more closely affiliated with other galleries?

No, I don’t see much of a difference. I think it all works out best when the galleries collaborate so that each artist distributes their work, their art and their exhibitions between the various galleries they work with. So our Danish artists don’t really have this as their ‘mother’ gallery. I’ve always been very keen for our artists to get gallery representation abroad because that might help strengthen them and their position. Of course, we compete with the foreign galleries who represent our artists because we take part in many of the same art fairs, but we also have a shared interest in having our artists do well. So the way I see it, admitting a good, new gallery to the circle is a good thing; they can help that artist reach new audiences and add new nuances to how they’re presented.

One of the things that helped establish establish your gallery internationally was the fact that you began to take part in art fairs abroad at an early stage. When did that begin?

Our first art fair was Art Cologne in 1994, and I think our first time at Basel was in 1999. Art Basel was the largest fair even then, but Cologne was a very close second, a fact that many have more or less forgotten today. That was where we first connected with the international art world, and I soon realised that this was the way ahead for us. Neither museums nor collectors in Copenhagen were particularly interested in us to begin with, so arriving in Cologne to suddenly find that people thought we were on to something was a big deal. For example, we met Nicolas Bourriaud while he was working on Trafficat CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux, the exhibition that canonised his ideas about relational aesthetics. Several of our artists were featured at that exhibition alongside huge international figures who were up and coming back then.

Jonathan Monk, “Exhibit Model Two” installation views, 2016

Up through the 1990s we attended quite a few fairs of a kind that hardly exists any more. Getting accepted to show at Art Basel is quite hard, and back then getting into Art Cologne was equally difficult, so a lot of smaller fairs were arranged in cities that didn’t have a major art fair already, such as New York. What we’d do was that a handful of galleries partnered with a hotel where you’d pay a relatively small fee for renting a room where you’d live and exhibit art at the same time.

This was a little impractical in some ways: for example, you couldn’t put nails in the walls, so you had to arrange the works on the bed and floor or settle for the nails that were already in the room. Some really good galleries used this approach, either because there weren’t any other fairs or because they were still up-and-coming and couldn’t get into, or afford, Art Basel. One of these hotel fairs would later become the present-day Armory Show in New York.

We took part in quite a lot of fairs like this in the 1990s, which really helped to boost our international presence. Back then, very little happened in Denmark, so when we set off for art fairs abroad we particularly wanted to establish an international market. We didn’t make fortunes, but something did happen: we actually sold some of the pieces we brought along, and – crucially – we formed a lot of contacts and carved out a name for ourselves abroad.

I have the impression that for many galleries today, most of the action still takes place at the art fairs. What’s it like for you? Might we say that after the first three hours at Art Basel, you more or less know what kind of year you’re having?

Yes, it’s still like that. Of course, different galleries navigate in different ways and have their main markets in different places, but Art Basel is insanely important to all the galleries who are there. I am aware that some galleries sell everything they bring along at the preview. Galleries work and position their artists in very different ways. I don’t know what my entire year will be like after three hours, but much of what happens over the course of any given year is based on something that was launched at a fair like Art Basel. In that sense, art fairs are of crucial importance.

Is the kind of very rapid, meteoric artist careers we see today one of the perils of the large art fairs and their tremendous impact on the business?

I don’t really think that the art fairs create those sudden flashes. I think they’re the result of many things, and no-one’s without blame in that regard. Galleries, art fairs, collectors, auction houses, museums and curators – they all take part in creating that situation. You cannot create hype out of nothing. Someone has to go along with it in order for that situation to arise.

I think it’s important to be aware of what you’re doing – as an artist and as the gallery counselling that artist. I sometimes see a cynicism that may always have been there to some extent, but which I definitely feel has grown stronger during my time in the business. An artistic career can be launched very quickly these days – and it can peter out as quickly too.

As a gallery owner, this must place you in something of a bind – on the one hand you’d like to have hype, but on the other hand you also need to be able to control it?

Absolutely! It can be a huge dilemma. You need to stay aware of what actually generates value in the long term. I’m not talking about money here, but about how to ensure that the artistic project will stay viable.

When you see a career taking off in a way that might not be for the best in the long term, what sort of strategies are available to gallery owners?

If you know that certain galleries and collectors are particularly well known for getting things to go off with a bang, you can quite simply avoid exposing your artists to those particular people. Conversely, if you know of someone – often a curator – who takes a more long-term approach to working with institutions, you might want to look to them more.

Do you think that your role is partly to protect your artists a bit from all the things that are not directly associated with the works themselves?

Alexander Tovborg, “hvem er dit sværd” installation view, 2018

The artists I work with are all very much aware of what they’re doing, but of course we have an ongoing dialogue. Sometimes it’s important to go up against the market, I think. Right now, for example, we have an exhibition featuring Alexander Tovborg. If he’d done twenty paintings measuring 1 x 1 metres each, we’d instantly have a sold-out show. Instead he’s done two paintings that are each six metres long. Of course, that’s not the sort of thing many people are looking for, but it’s what is important to do.

It’s a really difficult, delicate and interesting balancing act, and I completely understand why a young artist gets tempted if they have ten people lining up to buy their paintings. The contemporary art scene has plenty of exciting art of lasting quality, but there’s also a lot of stuff that looks as if it’s simply been made because there was a demand for it. Like I said, my original starting point was in art as something that’s created without anyone asking for it, and I still think that’s a hugely important point to bear in mind. And that can be difficult because of all the many temptations out there – not least your own greed.

What, to your mind, are the main differences between running a gallery back when you got started and today?

The main difference has to do with speed. Partly the speed of the market and of the artists’ careers, as we were just talking about. But also the rapid technological developments. They have completely changed the way that art is presented to audiences. Back when I first opened the gallery, communication involved someone sending a fax. That fax might say: ‘I like very much the work of Joachim Koester. Can you send some images?’ Then I’d take the original slide to a photo shop and have some copies produced, put them into plastic sheets and take them down to the post office. Approximately one week later that person would receive the slides. And then we were ready to begin a conversation. I hardly need to explain how different things are today where all communication is digital and those who request information practically expect it within minutes. Communication takes place at speeds that are quite insane compared to before. Even though I was right there, doing it myself, I can hardly believe that this was how things were done just 25 years ago.

We began by speaking about how the Danish art scene of the 1990s was quite small and how there was little interest in contemporary art. How would describe the same scene today, where contemporary art seems to attract very great interest?

There’s no question that the art scene of Denmark has become far more serious, professional and international. The state of affairs on the gallery scene right now is that many more galleries show contemporary art and have huge ambitions, showing excellent exhibitions featuring great artists that they represent on a long-term basis. Nils Stærk and our own gallery remain the most internationally active, but today you’ll find many Danish galleries looking out into the wider world.

“Inside Out” group exhibition installation view, 2016

This is a very welcome development, because competition helps keep us all on our toes. During my first years of running a gallery I always had this sense that mine was the best place in Copenhagen, and even though that’s nice in a way, I still felt a need for a wider scene around me. If there’s no-one around to see yourself reflected in or to challenge you, you can end up so laid-back about the whole thing that things get dull.

The institutions have seen more or less the same kind of development. The museums and art venues alike have all become far more ambitious than they were twenty-five years ago. Back then, academy graduates would work for years and years before getting shown at the museums; today that transition happens much more quickly. So they’ve gotten less cautious than they used to be.

Back in 1998, Århus Kunstmuseum (now ARoS) presented an exhibition called Farvel til 80’erne (A Farewell to the Eighties). I thought it was quite ironic that so many years had to go by before the Danish museums were ready to let go of the 1980s. There’d been this generation that had enjoyed extremely high visibility and which everyone had exhibited, and when new things emerged in the 1990s no-one really knew what to do with it. You could say that museums often lag behind their own times, but today you don’t see museums exhibiting only works by the 1990s generation – quite the contrary: museums today show plenty of contemporary art.

You often address cultural policies and politics in public, for example as a columnist for Danish newspaper Politiken. If you were to point out one initiative that would make a major difference for Copenhagen as an art city in the future, what might that be?

I think I’ve moved on a bit from thinking that a large new institution is the answer to our prayers. I actually think the real issue has to do with our mentality – with our levels of education and thinking about art. I think that what Denmark needs is a new group of intelligent politicians that can be recruited as ministers. I am appalled at how the Ministry of Culture is still the least prestigious ministry in Denmark. ‘Minister’ means ‘servant’, and very few of those who have held the position as minister of culture in recent decades have acted as servants to art and culture.

If I were to make a wish, it would be to hand over the Ministry of Culture to someone with actual ambitions within the field. Making a real difference on the Danish art scene is not just a matter of funding, but about having certain ambitions about the kind of direction we want for our society; an outlook that is not just preoccupied with balancing figures and making ends meet financially, but which also reflects a belief that art and culture can help us grow mentally. If we don’t have art and the insights it can bring us, the rest does not matter.